Visibility After Dark: Four Photos from William Como's Archives

To celebrate Public Sale’s offering of photographs from the archive of After Dark and Dance Magazine editor William Como in our upcoming auction After Dark & Clean Lines, we examine four photographs by the magazine’s most celebrated photographers Kenn Duncan and Jack Mitchell, and a story they tell about the role of visibility in the struggle for gay rights.

After Dark’s contribution to the mainstream visibility of gay culture cannot be overstated. The magazine, which writer Daniel Harris called “an audacious mass-market experiment in gay eroticism,” featured revealing photographs of male models, dancers, actors, musicians, and bodybuilders in a way that celebrated gay culture and catered to a ritzier segment of its demographic without drawing too much negative attention, thereby paving the way for more risqué publications. Sam Stagg, former editor in chief of three such titles, Mandate, Honcho, and Playguy, described After Dark’s dance-like navigation of the line of decency this way:

“After Dark was bold and beautiful. It titillated like a strip tease, meaning it didn't emerge from the closet even though each issue grew bolder as men's tights and trunks dropped a few centimeters, bulges bulged, biceps and quads and glutes flexed and gleamed, and Kenn Duncan, the magazine's foremost photographer, created an unmistakable look that influenced gay imagery for years to come.”

“After Dark was as closeted as the gays had to be then,” says one collector of gay periodicals in Frank Rizzo’s account of "When gay culture winkingly slipped into the mainstream". “Still, if you were a closeted gay man, you just knew the magazine was for you. But for others, it usually went right over their heads.” Rizzo poetically describes his own first encounter with the magazine and how it offered a feeling of being seen on an individual level: “ It was as if I just shook hands with my secret self.”

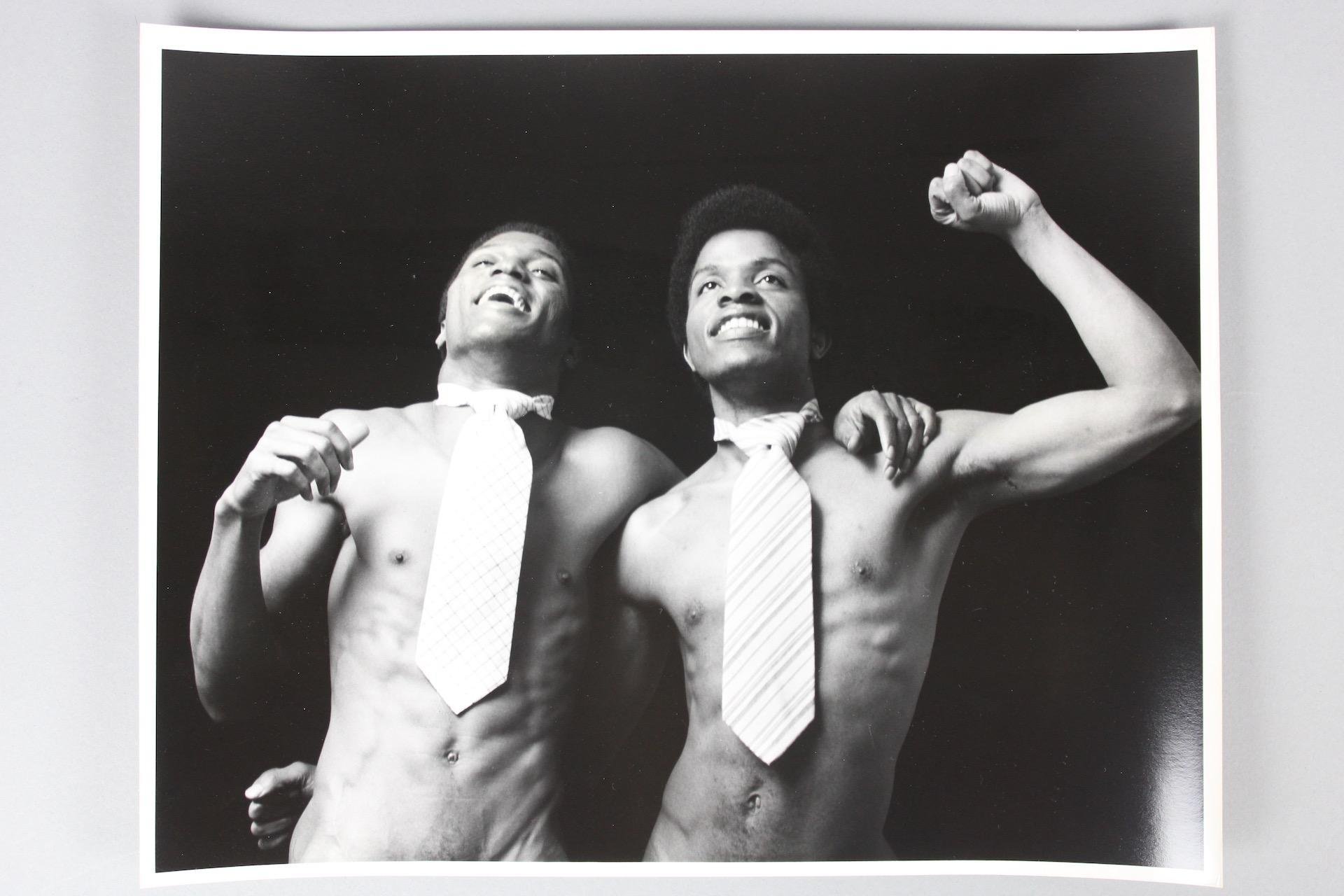

Witness Kenn Duncan’s photograph of what may be two dancers from the Alvin Ailey company or Dance Theater of Harlem circa early 1970s:

Lot 925: Kenn Duncan Photographs; Portrait of Shirtless Black Models Wearing Neck Ties 2 of 3.

This photograph, showing two Black men wearing nothing but neckties smiling, laughing, and seeming to lift their fists in the air, would have been taken not long after another photograph of two Black men with neckwear and hands raised: the iconic John Dominis image of gold and silver-winning athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos during their medal ceremony at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. One wonders what specific direction created this moment in Duncan’s photo studio, though its sense of playfulness, evoking the Olympics moment with a salute as much to Black Joy as Black Power, is common to much of Duncan’s work for After Dark.

Activism is even more explicit in another photograph by After Dark regular Jack Mitchell:

Lot 646: Jack Mitchell Photographs; Michael Sira Male Model Wearing Protest Shirt.

The model here wears a T-shirt from the Miami Victory Campaign, which centered around the highly publicized effort to repeal a Dade County ordinance that protected homosexuals from discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodation. Celebrity singer Anita Bryant was the leader of the anti-gay coalition called Save Our Children, which based its advocacy on conservative Christian beliefs about homosexuality’s sinfulness and recruitment of children. When the photo was taken, viewers would have recognized this shirt’s slogan as a play on the tagline of the Florida Citrus Commission, voiced in nationally televised commercials by one other than Anita Bryant, its paid spokeswoman: "Breakfast without orange juice is like a day without sunshine." The young man stares into the camera defiantly, with hands behind head in a pose that doubles as a subtle flex of muscle, visible with rolled-up sleeves. Yet hidden in this defiance is a plea for inclusion, seen in a facial expression that suggests not so much hostility as a kind of earnestness or sincerity, underlined below by a necklace that appears to be intentionally displayed over the model’s shirt, bearing on its end a large crucifix. This image, like the struggle it represents, is a complicated one.

When Miami’s gay protections were repealed, the NYT reported that Anita Bryant “celebrated the victory by dancing a jig at her Miami Beach home.” But a leading figure in Miami’s gay community Robert Kunst remained undeterred: “We started from ground zero and got around 100,000 people to support us…This is just the beginning of the fight.” Indeed, history would seem to vindicate Kunst over Baker, and the community of artists whose powers of dance could put Baker’s victory jig to shame. In 1998, the Miami-Dade County Commission reinstated the ordinance; in 2003 the Supreme Court struck down U.S. sodomy laws; in 2004 the Miami-Dade circuit court overturned a Florida statute forbidding gay adoption; and in 2015 the Supreme Court granted same-sex couples the right to marry.

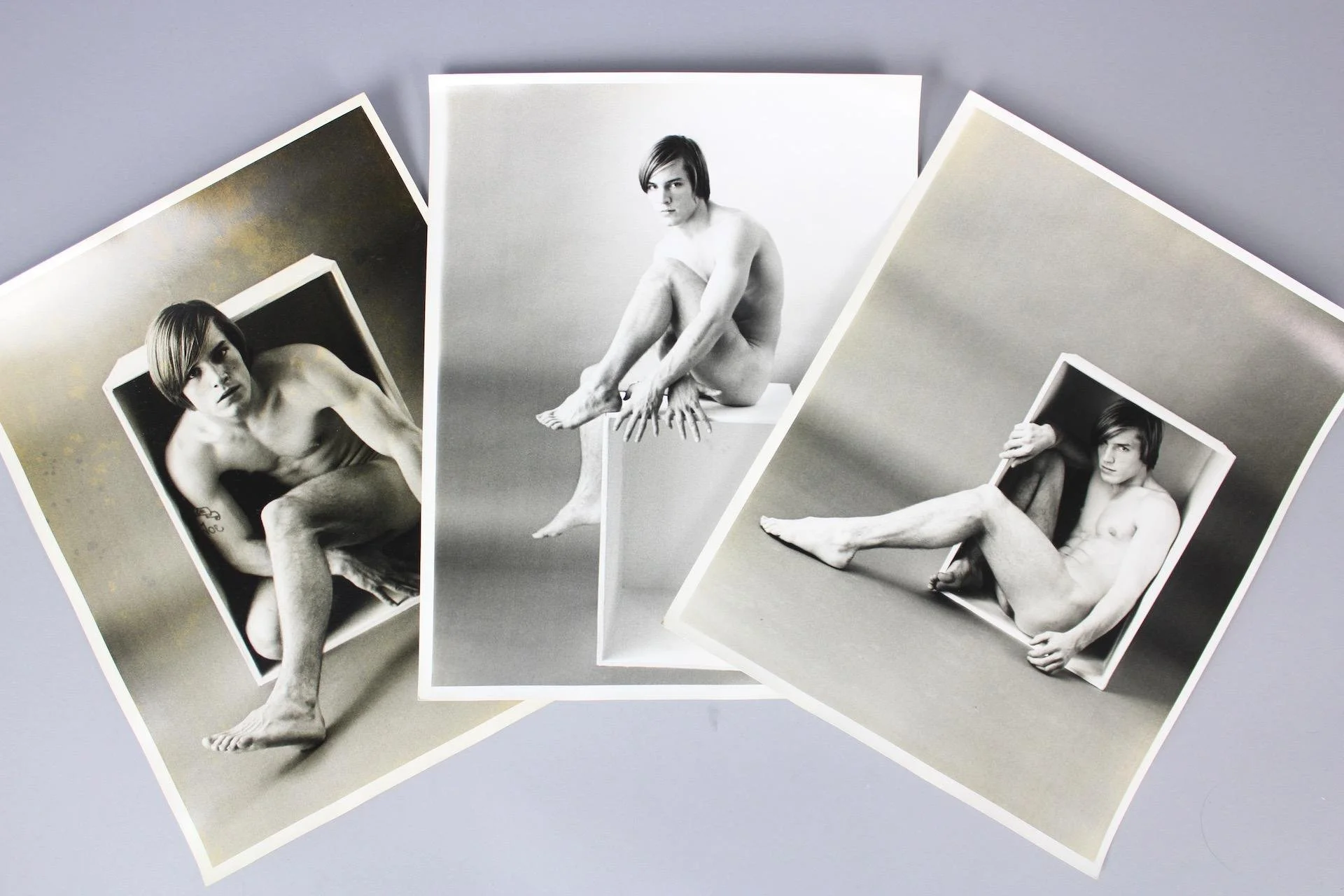

Considering these advances in gay rights, let us return to more work of Duncan’s:

Lot 759: Kenn Duncan Photographs; Nude Joe Dellasandro in a Box.

In this series of three photographs, a young and fresh-faced Joe D’Allesandro, model, actor, and Warhol “superstar,” is pictured in three positions in relation to a box. A box is not an uncommon prop in the studio of a photographer, allowing models or objects to be conveniently set upon it. In this case, D’Allesandro is going a step further and interacting with the open-sided cube as both a space of confinement and a platform. Given the history and politics of identity surrounding Duncan’s body of work for After Dark, this box may begin to take on the qualities of a closet. In one image, the young man seems to cower inside the box, his gaze averted downward, one hand clutching its side as if feeling its limits, one leg dangling out as if in search of a foothold. In another, he begins to emerge from the box, his head free, hands feeling, eyes cast forward. And in the third photograph, he sits perched atop the box, with widely stretched fingers that draw attention to the box while also covering his genitalia. He gazes at the camera, but with a face still slightly downturned like the expression he had inside the box.

It’s as if the visibility won through struggle comes with some loss. Rizzo, who recognized his “secret self” in After Dark, poignantly observes how the publication “bookended two LGBTQ landmarks and was a chronicler of that special time of liberation and innocence. The magazine that began just before Stonewall [went on to publish] its final issue in January 1983 – one month before The New York Times Magazine reported on the birth of a new disease called AIDS.”

Duncan himself would later die of complications of the disease, as would many of the subjects he photographed. And Daniel Harris, who noted After Dark’s audacity in 1997’s The Rise and Fall of Gay Culture, also noted how gay culture’s movement into the mainstream had undermined the distinct subcultures of the gay minority. “The fact that we have achieved a high degree of visibility does not mean that gay culture is flourishing. In fact, what we are seeing is that we are on the verge of assimilation and that assimilation will ultimately result in the obliteration of gay culture.” Though Harris’s prediction of obliteration sounds exaggerated, it may be difficult for some to look through the pages of After Dark, and not feel some sense of loss for the rich culture that once grew and thrived in an atmosphere of oppression and secrecy.

With that bittersweet feeling of how far things have come, and how far things still have to go, we might consider a final photograph from Como’s archive, another by Mitchell.

Lot 723: Jack Mitchell Photograph; Warhol Superstar Candy Darling for After Dark Magazine.

This photograph of actress and Warhol superstar Candy Darling was used for the cover of the September 1972 issue of After Dark. Darling died just two years later, from a lymphoma some link to hormone complications. Here we see a radiant Darling sitting atop a stool with legs crossed, one arm folded loosely over knee and another framing her face, in a relaxed yet searching pose, wearing a small black slip and an expression of simultaneous confidence and vulnerability. Her look invites us to consider what was lost in her death, and the losses suffered in the gains in the ongoing struggle for gay rights, which the previous model’s shirt reminds us are human rights—especially today as we hear the same arguments of Baker’s Save Our Children campaign echoed in the controversy over trans rights.

We might all do well to take after Darling’s own mother, who once, in Warhol scenester Gary Comenas’s telling, before she left for New York City and became the icon“confronted her about local rumors, which described Darling as ‘dressing as a girl’ and frequenting a local gay bar called The Hayloft. In response, Darling left the room and returned in feminine clothing. Darling's mother would later say that, ‘I knew then... that I couldn't stop [her]. Candy was just too beautiful and talented."

We might also consider the words of Candy as immortalized in the Velvet Underground song inspired by Darling. The song’s verses name things “Candy Says” she hates, before opening to a chorus that offers some kind of escape:

"I've come to hate my body / And all that it requires in this world"

"I hate the quiet places / That cause the smallest taste of what will be"

"I hate the big decisions / That cause endless revisions in my mind"

"I'm gonna watch the blue birds fly / Over my shoulder

I'm gonna watch them pass me by / Maybe when I'm older,

what do you think I'd see If I could walk away from me?"