Folktales

The first snow of the year had barely melted when the posters began to appear around town:

An Auction of Folk Art, Quilts, Sculpture & Handmade Wonders

January 17

At first, people thought it was just another sale—another chance to trade old things for new money. But this auction was different, because everything in it had a story, and the stories were starting to wake up.

The auction house sat in a low metal building that used to be an Oldsmobile dealership. Its worn cement floors remembered every footstep, and its tall windows gathered whatever light the winter sky was willing to lend. On the morning of the auction, you unlocked the door, flipped on the lights, and the place came alive.

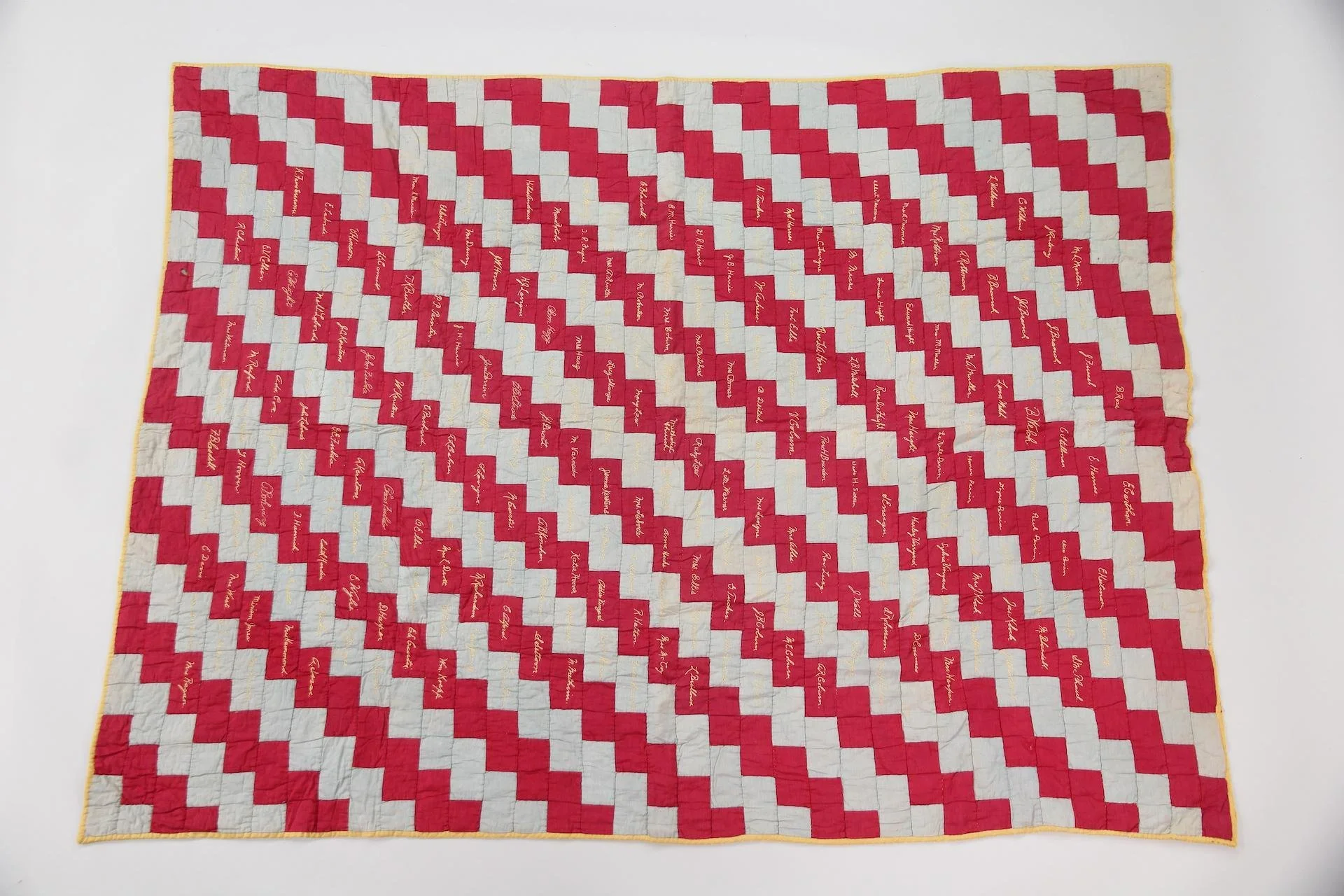

The first thing you noticed was a quilt you’d hung right by the entrance. It was a signature quilt, pieced from scraps of worn-out work shirts, a faded rose-print dress, a child’s pajamas, and even a strip of red feed sack. Some pieces were frayed, some nearly new. The colors didn’t technically “match,” but somehow they belonged together anyway. Hand-quilted stitches wandered a little, like a path found in the dark.

You’d tagged it:

Lot 128 – “Folk Art Zig Zag Signature Quilt”

Unknown maker, This quilt is made of hand pieced red & white rectangles arranged in a zigzag pattern, with chain stitched yellow signatures and yellow muslin back. Possibly a Southern quilt, as one signature reads "Pensacola, LA, 1938" Hand quilted. Family lore suggests it was sewn during long winter evenings by lamplight.

What the tag didn’t say was what you knew in your bones: this quilt had heard stories for decades. It had been spread on floors for children’s games, pulled over sleepy shoulders, folded carefully for guests, laid across laps during nights that felt too long.

When you lifted it to straighten the edge, you could almost hear the echo of laughter, of arguments that ended in forgiveness, of hushed voices sharing secrets after the rest of the house was asleep.

Near it stood two hand-carved beavers. One wood painted in layers of brown and black, its eyes a swirl of white and blue. It wasn’t symmetrical; the tail was a little too big, and the tooth was slightly crooked. That imperfection made it feel more alive. One carved stone by an inuit artist..

Pair of Carved Folk Art Beaver Figures, Bradford Naugler & Inuit. Includes a carved and painted wooden beaver, with a great expression, signed by the folk artist Bradford Naugler (b.1948.) The second is carved stone by an Inuit artist, signed by Steve John.Carved and painted by hand. Local legends: the beavers that never slept.

Rumor had it, the old artist who carved it kept it in his kitchen window. He’d whittle away at it while sitting at the table every night after his chores, telling it that real beavers were hard workers, but always stayed hidden, but a wooden one would always stay in sight. Maybe that’s why it seemed to stare straight at the door, waiting.

Against one wall, you’d arrange a row of hand-built sculptures, traditional yet not-so-traditional: an iron devil with bright red horns, a long haired monster, hands raised above her head made from old metal scrap, a carved face that looked halfway between sorrow and laughter. Another ghoul was popping out of a box! Some of them had mechanisms that showed they used to come to life, used to amuse young and old visitors to a fair in Pennsylvania.. and yet they were rough, still holding the memory of the maker’s hand.

Amusement Park Folk Art Iron Devil and Ghoul Sculptures. This fantastic iron sculpture of a devil has horns and a smiling face, with worn red, blue, & black paint. From a Pennsylvania amusement park. Said to have spooked all who witnessed them for over 70 years.

The Skeleton’s eyes were not quite even, and there was a crack down one cheek, but it had the calm presence of someone that had seen all kinds of weather and all sorts of people go by.

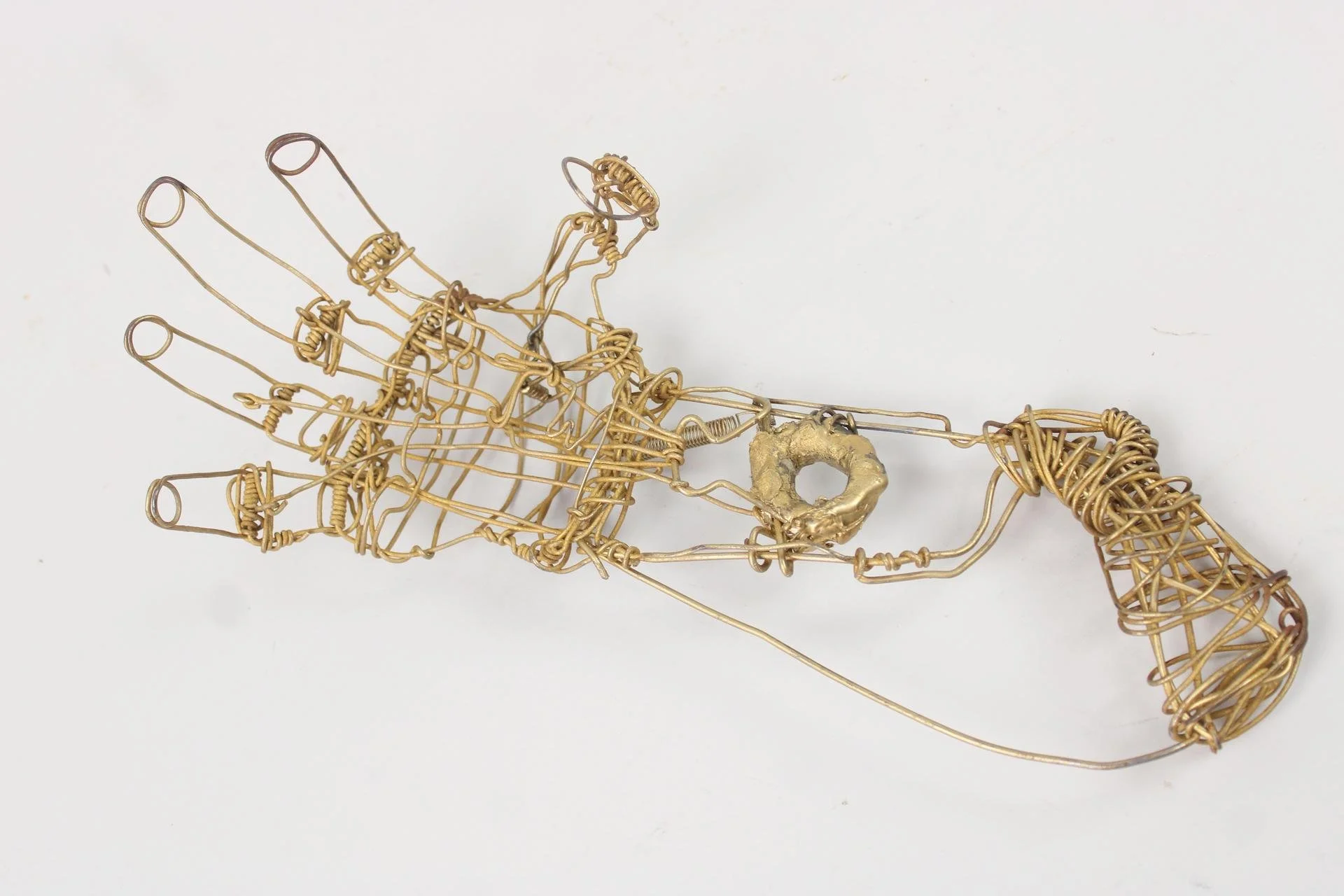

On the long tables in the middle of the room, you’d lined up handwoven baskets, tin toys with chipped paint, hooked rugs, hand-painted signs, and small pieces of sculpture made from anything the artists could find: dogs made from markers and masking tape (240, 242, 246), birds from shells (336,) hands from wire and paint (347.)

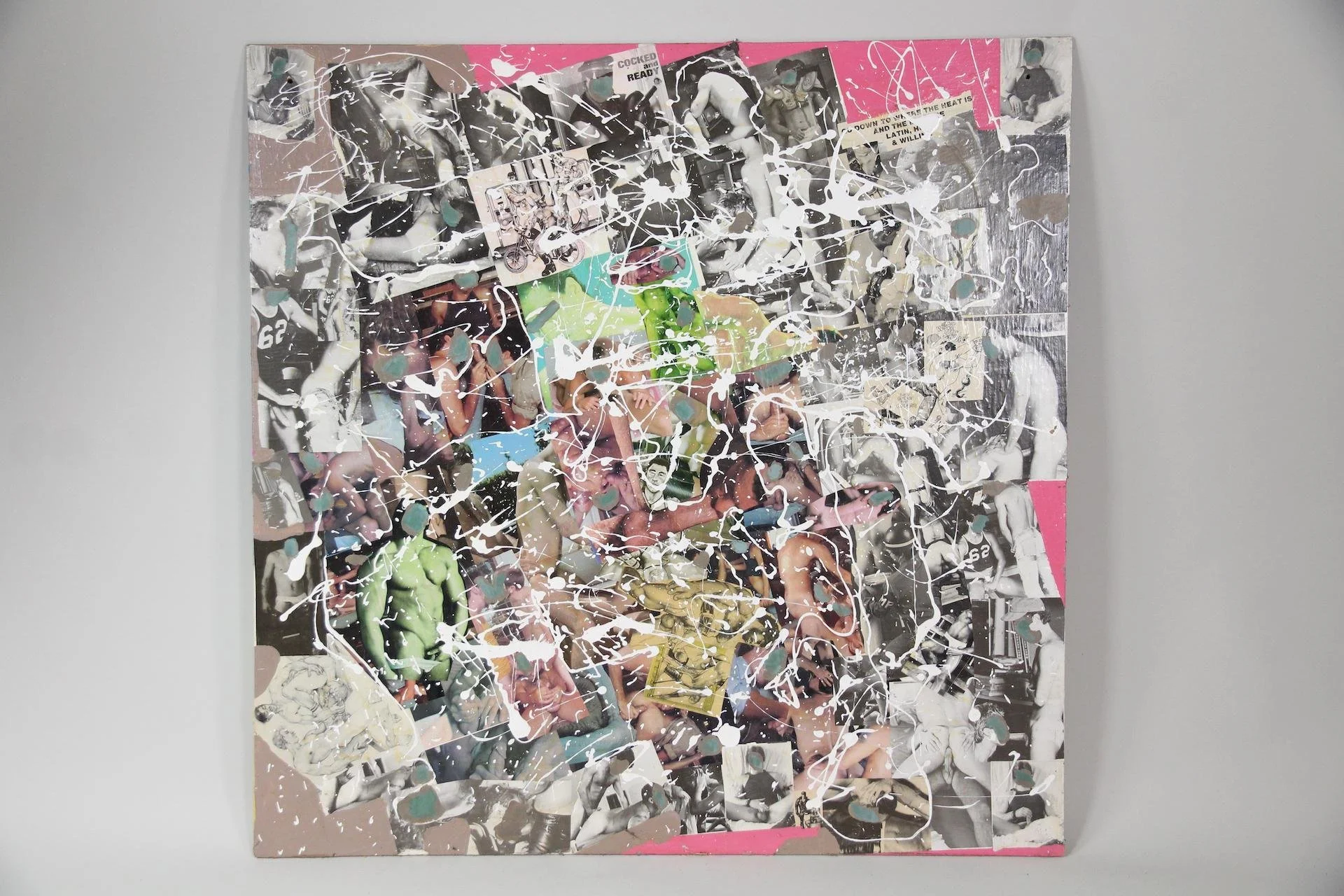

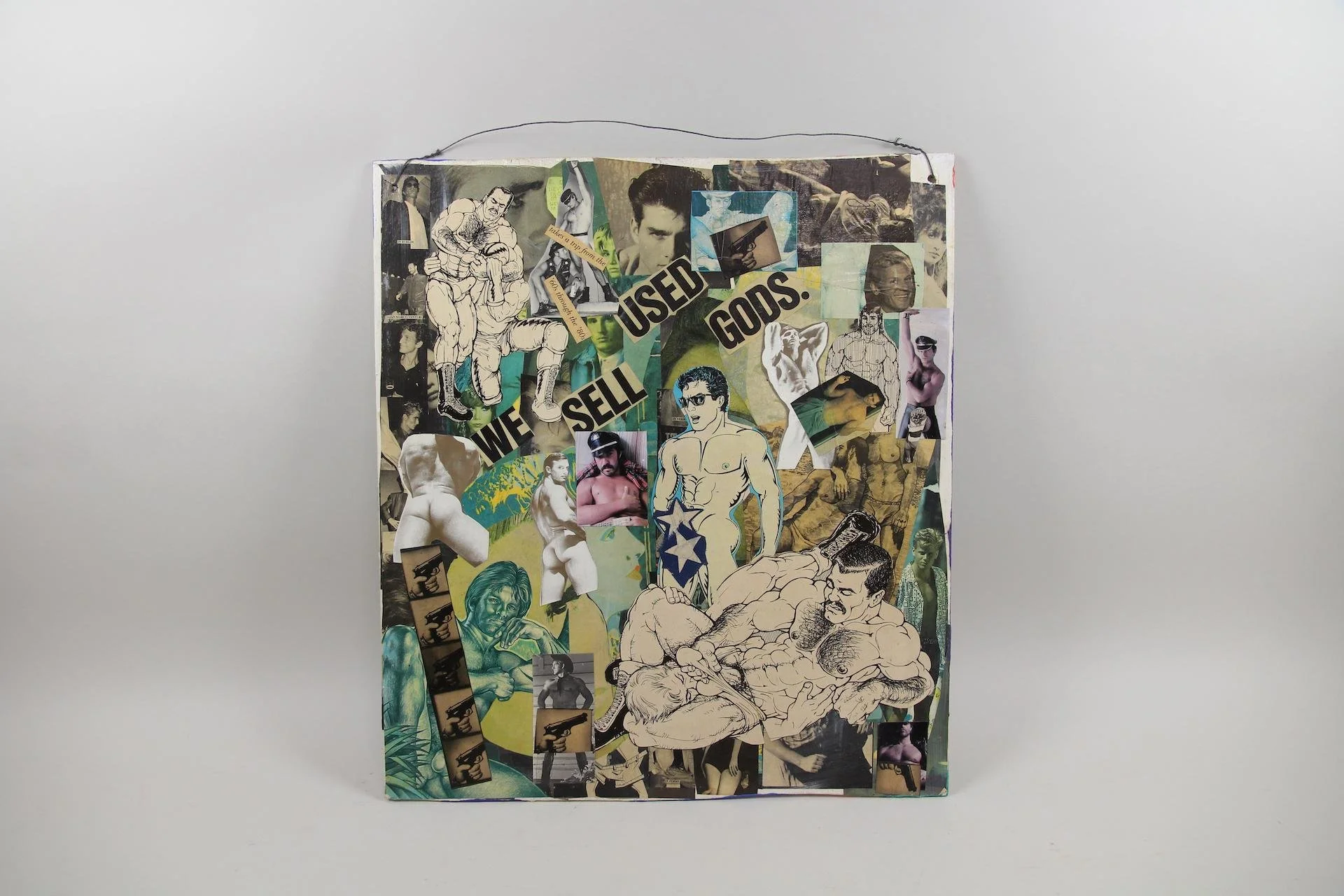

Some pieces were “antiques” by any official measure—over a hundred years old, with provenance and history. Others were too new to be called that, but just as full of character: a bright, wild collage made from the 1980s made with magazine and book pages (72, 73, 74, 75); books of photographs showing the rich traditions and culture of appalachia that still exists in the 21st century (Lots 62, 63), a chair made from horns and rawhide (14); a coat rack that was once a cane (260).

You’d decided long ago that “traditional” and “nontraditional” were not enemies. In this auction, they sat side by side, telling one big story.

As people began to arrive for preview—faces red from the cold, hats dusted with lingering snow—you felt the energy in the room shift. This was the first auction of the year, the first gathering, the first time people had come out after the long quiet of the holidays.

They came for different reasons.

An older woman in a wool coat walked slowly along the quilt rack, fingertips brushing the edges. She stopped at a simple three-patch quilt pieced from blue and white shirts.

Lot 127 – “Hand Quilted Folk Art Wholecloth Quilt, Red & Cream”

Maker unknown. Cotton. Found in a trunk in a farmhouse attic.

You saw her tighten her lips, like she was holding back tears. Finally she whispered, more to herself than to anyone, “My mother had one just like that. She’d lay it out on the line every first good day of spring.”

She took a bidder number.

A young couple, paint still on their hands and jeans, wandered toward the sculptures. They moved quickly, pointing out pieces to each other: the wooden fish, the fiberglass deer, and wild, abstract face made into ceramic jugs.

“This one,” the young woman said, touching a small ceramic tiger “I want this one for the new shelf.”

They, too, took a bidder number.

A man in a suit, clearly more comfortable in boardrooms than barns, stood sternly in front of a carved wooden chest, his eyes sharp and calculating.

Lot 395 - “Green Painted Wood & Iron Trunk, Colony Club Pittsburgh“

A lidded trunk with patinated green paint and white lettering that reads "Colony Club, 10, Pittsburgh."

He wasn’t thinking about the stories in the paint, but about “investment potential.” Even so, the chest would go home with him and carry his own story one day, whether he realized it or not.

More people came: collectors, dealers, neighbors, someone drawn in off the street by the sign in the window. They moved among the lots, and the objects seemed to shift in response—quilts catching the light more brightly, carved faces softening, brush strokes in the folk paintings seeming to deepen.

You stepped up to the podium, gave the microphone a small test tap, and the talking in the room collected itself into a hush.

“Welcome, everybody,” you said. “To Folktales—our first auction of the year. Everything in this room was made by someone’s hands. Some of the makers signed their work. Some never imagined anyone would speak their names. But they all left something behind that still speaks for them. Today, we’re not just selling objects—we’re passing stories from one set of hands to another.”

There was a murmur, a few nods, the click of pens on catalogs.

You began.

The early lots went quietly but steadily: a painted farm scene, a hooked rug with triangles and stars, a carved walking stick with a snake curling up its length. Bids rose and fell, paddles lifted and lowered. The rhythm of an auction is its own kind of music.

Then you came to Lot 127 – “Hand Quilted Folk Art Wholecloth Quilt, Red & Cream”

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is a hand-sewn whole cloth quilt, early-20th century, made from clothing fabric. It’s seen some life, but it’s still strong. We’ll open at fifty dollars. Do I have fifty?”

The older woman in the wool coat raised her paddle immediately, her hand trembling slightly.

“Fifty,” you said. “Do I have sixty?”

A collector at the back lifted his number. He loved old textiles, loved the value in them.

“Sixty. Seventy?”

The woman in the coat didn’t hesitate. “Seventy.”

You watched the dance: seventy, eighty, ninety. The bids went back and forth, and each time, the woman’s face tightened a little more, as if she were arguing with someone inside her head—maybe an accountant, maybe a memory.

At one hundred and ten, her hand wavered. You felt, in the way auctioneers learn to feel, that this was the edge of what she could manage.

“One hundred and ten I have,” you called. “Do I hear one twenty?”

She clutched her bidder card, knuckles white.

You could not change the rules of bidding, but you could offer a moment.

“Remember,” you added, voice gentle but carrying, “this quilt isn’t perfect. It has a small mend here, and a little fading in the center. It’s lived. That’s part of its charm, and, in my view, its value. One hundred and ten, going once…”

The collector at the back hesitated, eyes narrowing at the word “mend.” He lowered his paddle just a fraction.

“Going twice…”

The woman in the wool coat raised her card again, just barely, like a last whisper of hope.

“One twenty,” you said quickly. “I have one twenty. Do I hear one thirty?”

The collector hesitated, then shook his head, closing his catalog.

“One twenty, going once…going twice…sold.”

The room let out a breath they didn’t know it was holding. The woman smiled, but it was the kind of smile that comes with tears. You knew she’d take that quilt home and lay it across a bed or a couch, and for her it would not be “Lot 28” anymore. It would become a bridge across years, connecting her to that line of quilts flapping in the first spring breeze.

Lot 556 – “Pair of Carved Folk Art Beaver Figures“

“These handsome fellows,” you said, “were carved by hand, probably by a men with more ideas than money. They say the wooden one watched from the kitchen window and never let the coffee burn. We’ll start at thirty.”

Hands went up quickly. The beavers' expression made people grin. It was ridiculous and proud, stubborn in the way only a wooden beaver can be.

As you called the bids—thirty, forty, fifty—you swore you saw something shift in its painted eye, a spark of satisfaction. It was being wanted again. It would have a new window to watch from.

The more nontraditional pieces surprised you.

“Is this really folk art?” someone whispered.

You answered from the podium, as you introduced the lot. “Some people say folk art must follow old patterns, old ways. I think folk art is what happens when people use what they have, where they are, to say something with their hands.

Lot after lot passed under the warm gaze of the room:

– A naïve painting of a farm with a bright red barn that was slightly too large for the landscape.

– A patchwork rug that used such loud, clashing modern fabrics became unexpectedly beautiful.

– A tiny hand-carved horse no bigger than a cat, its figure barely indicated by the knife.

– A set of embroidered kilim pillows worn thin but still lovely.

Sometimes the antiques drew fierce competition, their ages verified, their styles recognized. Sometimes a newer craft piece, made by someone ignored in their own time, lit a bidding war because its personality refused to be overlooked.

Near the end of the day, when people’s shoulders had relaxed and the room was full of that special kind of tired satisfaction, you came to Lot 356 – The Skeleton.

The assembled figure sat quiet and steady hanging from a beam.

“This,” you said, “once spooked kids and adults alike. It’s not polished. It’s not perfect. But it has the presence of something that’s stood through storms. Who’ll start me at seventy?”

At first, silence. Then the young couple from earlier—paint still faintly on their fingers—raised their paddle.

“Seventy,” you said.

An older man with a weathered face, the kind that had known sun and work, slowly lifted his number.

“Eighty.”

The couple looked at each other. The young woman shrugged.

“Ninety,” the man said.

“One hundred,” the older bidder replied.

You watched something unspoken pass between the three of them. This wasn’t about investment or matching décor. It was about wanting a guardian, a witness in metal.

“One twenty,” the young woman said, her voice steady.

The older man paused, then smiled, surprising you. He lowered his paddle and gave them a small nod, like passing a torch.

“One twenty,” you said quietly. “Going once…going twice…sold.”

The room, by then, understood. They applauded, not just for the sale, but for the way the story had chosen its next chapter.

By the time the last lot was sold and the crowd began to thin, the sky outside had turned the pale blue of early evening, that in-between color that happens just before the first stars appear. People left carrying quilts gently cradled in their arms, sculptures tucked under coats, paintings wrapped in paper, small antiques carefully boxed.

In their hands, the objects were no longer “lots.” They were part of someone’s home, someone’s new beginning for the year.

You moved through the room, checking tags, making notes, answering questions, arranging pickups. When at last everyone was gone, you turned off the microphone and stood quietly in the middle of the empty auction house.

The tables were scattered with the impressions of what had been: faint rings where coffee cups had rested, scuffs from chairs, the one little paper sign that had fallen to the floor.

But in your mind, the room was still full: the smell of old wood and new paint, the murmur of voices, the sharp rhythm of your own chant calling bids, the small gasps of delight when someone won something they wanted more than they’d admitted.

You walked to where the Folk Art quilt had hung and touched the bare hook. Somewhere tonight, it was already spread out in a warm lamplit room, its stories unfolding again.

On a new windowsill, the beaver would be watching traffic instead of tractors, but he’d still be on duty before dawn.

The sea shell bird would hang over a musician’s studio door, catching the light, its shell-wings turned into symbols of grace.

The skeleton would stand in a freshly painted house, keeping an eye not on an old fair but on a city street, watching different storms, different joys.

You locked the door and stepped out into the cold evening air. Your breath rose in a small white cloud, joining the fading day.

The year was just beginning. There would be other auctions—different collections, different themes. But this one, Folktales, felt like a promise: that hand-made things, whether traditional or wild, antique or newly born, would continue to find their way from one heart to another.

You thought of something you’d said at the beginning, almost without planning it:

“We’re not just selling objects—we’re passing stories from one set of hands to another.”

Out on the quiet street, you realized that was what your auction truly was: not just a marketplace, but a crossroads where folk art, quilts, sculpture, antiques, and crafts collided with new lives. A place where the first day of the year wasn’t about starting over from nothing—just turning the page to the next chapter.

Behind you, the dark windows of the auction house reflected your figure for a moment, then faded as you walked away. Inside, the old cement floor—like all the pieces you’d sold that day—remembered. And the stories, now scattered in houses and apartments and studios all over town, had only just begun to speak.