The Secret Message of Quilts

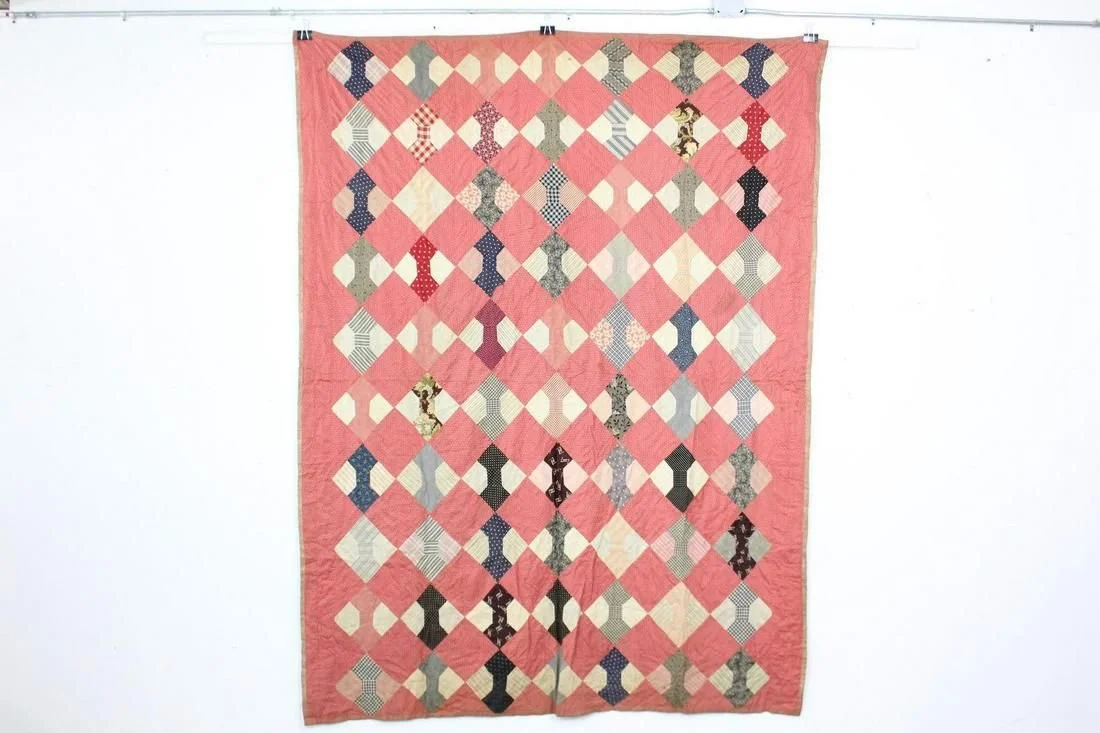

Public Sale’s upcoming auction, titled Life In America, features several antique handmade quilts. Many of these display the patterns that have come to be mythologized as part of a secret code used by escaping slaves during the Underground Railroad. Like the “bowtie” pattern (Lot 49) said to advise escapees “to travel in disguise or to change from the clothing of a slave to those of a person of higher status,” or the “North Star” pattern (Lots 178 and 254) said to reference the general northward direction of travel.

The idea that quilt patterns conveyed such messages gained popularity in the late 1990s, after the book Hidden in Plain Sight: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad was featured on the Oprah Winfrey show. The debate within the community of skeptical historians came to a head in 2007 during the installation of a statue to Frederick Douglass in Central Park, the design of which was to solidify the legend through the inclusion of a quilt rendered in granite.

While some ancestors of slaves have given oral histories, and many participants in the quilting tradition offer their own anecdotes, skeptical historians have pointed to a lack of solid evidence of the practice. Henry Louis Gate, Jr. once called the idea of quilt codes “one of the oddest myths propagated in all of African-American history,” adding that “if a slave family had the wherewithal to make a quilt, they used it to protect themselves against the cold.” Still, the legend has continued among contemporary quilters who see themselves as honoring a legacy.

Antique and vintage quilts today have become collector’s items, and deservedly so. Quilters are indeed carrying on a legacy—by the simple act of quilting. Quilts don’t need to be turned into some kind of carriers of arcane knowledge to be appreciated. They are objects with an exceptional combination of utilitarian and aesthetic qualities. They have a kind of dignity, signifying the patient labor of creative and resilient women—for whom the act of quilting probably had its own benefits, regardless of the outcome of any single piece, let alone how the quilts may have been used.

And the same can be said of the wider cultural practice of quilting at large. What a quilt embodies—an act of care, of creativity, of resourcefulness, mending, and repair, of empathy and comfort-making— is already inherently radical. We might even call it heroic, considering the harsh conditions in which so many of these soft textiles were produced.

This message that quilts carry is not so much secret as under appreciated. You don’t need to be able to recognize some code to feel the warmth of a blanket, or to experience the sublime in a combination of color and pattern. You only need to let it envelop you.